The trip is recorded in two books, Letters from the Southwest, a modern collection of the weekly letters he sent back to an Ohio newspaper, and A Tramp Across the Continent, Lummis's own prepared account of the trip published in 1892. The blurb I read about the tramp enticed me to seek out Letters from the Southwest, by promising that the letters would, "more closely reflect the author's thoughts and observations on the trail and that offer a more candid look at the Southwest than Lummis was later to bring to print." Sold again.

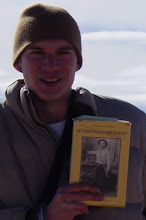

The trip is recorded in two books, Letters from the Southwest, a modern collection of the weekly letters he sent back to an Ohio newspaper, and A Tramp Across the Continent, Lummis's own prepared account of the trip published in 1892. The blurb I read about the tramp enticed me to seek out Letters from the Southwest, by promising that the letters would, "more closely reflect the author's thoughts and observations on the trail and that offer a more candid look at the Southwest than Lummis was later to bring to print." Sold again.So I turned to the web and sought out Letters from the Southwest. Let me tell you, Letters is not a New York Times bestseller. It's not a popular favorite on Amazon.com. In fact, its kind of hard to find anywhere. I ended up having to order it directly from the publisher, which happend to be located at my alma mater, The University of Arizona Press. The asking price of Letters was pretty far out of my zone of comfort for a book, and I literally hestitated before finally pulling the trigger. Buying Letters from the Southwest: $45 plus shipping. Creeping people out at the coffee shop when you whip out this cover: priceless.

Let's get down to some of the technical aspects of "The Tramp."

Lummis set out from Cincinnati, Ohio for the small town of Los Angeles on September 12th, 1884. The picture on the cover of the book is a promotional photo taken just before he set out.

Lummis made the walk from Ohio to Los Angeles by walking mostly along the railroad tracks (sometimes on, sometimes along the side if there was a path). Some exceptions to this were short cuts to save distance, and side trips. I imagine this was the only way it was feasible to make a cross country walk like this alone in 1885. Walking along the railroad tracks did many things for him. First and foremost it gave him a road to follow so he wouldn’t have to concern himself too much with navigating and risking getting lost. But even traveling by this method he recounts with surpringly fierce anger instances where he was given bad directions, causing him to get lost (in some cases dangerously lost) and walk many extra miles. Lummis reserves most his ire for two classes of people: people ungenerous about giving him a place to lay down for a night, and people who give inaccurate directions (willfully he usually speculates).

The railroad tracks also gave him, when nothing else was available, at least a decent walking path through all this rugged territory. Although, as Lummis makes notes of in his letters, not all railroad tracks are created equal in terms of walking. Two common problems were snow and ice on the tracks, and tracks set with large, jagged stones, which were very difficult to walk on and tore up his shoes (he notes having to have his shoes resoled many times, although he's very proud of how well the leather uppers held up).

Following the tracks also gave him some degree of assurance of food and shelter each night. Although the interval varied depending on the territory, he could expect to find a section house about every 10 to 30 miles or so. A section house was used by the local railroad crew tending that section of the track. The actual accommodations might vary considerably, but usually they consisted of a bunk house or two, a small kitchen, and maybe a small house for the foreman. Although, as Lummis noted with some consternation, they might sometimes be nothing more than a shed. At the section house he could beg for a space in the bunk house (sometimes denied him), and purchase dinner if available (although frequently, as he notes, at exhorbitant prices, especially in the more remote locations). If all else failed (which was not such a rare occurrence), he could build a shelter and fuel a fire with wooden railroad ties, often found in piles along the side of the track.

Lummis thought of himself as a well-conditioned athlete-- not a backpacker. His interest was not in hauling around all the gear he needed to be completely self sufficient: he was comfortable trusting in his luck and the railroad for his next meal or next drink of water. For example, he says he only started carrying a water bottle once he entered the desert, and it took a dangerous experience to teach him the necessity of this. He only carried small trifles of food with him if anything.

Not that he was without impressive survival abilities. This is a man who broke his arm in a very remote area of Arizona, set it himself, then walked 52 miles straight to Winslow. Lummis was also a passionate hunter, a useful survivial skill, and an important way that he experiences the West during the tramp. He often makes note of the change in game or the availability of game in his letters. This was definitely a big part of the fun for Lummis. I think of it a little like an avid golfer experiencing California through playing different holes of golf. It's worth noting that some of the most dangerous situations he found himself in were the result of hunting excursions.

Consequently, he ate a lot of meat he hunted himself, and he was not an entirely picky eater. He praised the virtues of the praire dog for eating, and wondered why the locals thought it unfit. He hunted and ate a lot of rabbits. He periodically took larger game like deer. He was estatic the first time he got a chance to hunt antelope. Of course, he wasn’t usually in a position to process a whole deer, especially when he was out alone and one of his prey had lead him way into the sticks. So several times he killed a deer and then carved a few pounds of steak from it and carried on his way.

Consequently, he ate a lot of meat he hunted himself, and he was not an entirely picky eater. He praised the virtues of the praire dog for eating, and wondered why the locals thought it unfit. He hunted and ate a lot of rabbits. He periodically took larger game like deer. He was estatic the first time he got a chance to hunt antelope. Of course, he wasn’t usually in a position to process a whole deer, especially when he was out alone and one of his prey had lead him way into the sticks. So several times he killed a deer and then carved a few pounds of steak from it and carried on his way.

All in all, “pounding the ties” was the most convenient method for Lummis to see the country by foot, and requiring the least advanced planning. What Lummis was doing was incredibly dangerous, but his letters are not about highlighting how dangerous the journey is. In fact, Lummis's attitude seems to be that he has it easy compared to the rugged pioneers who made the trip decades before him along the Sante Fe Trail and other western routes. Lummis is writing from the perspective that the country has been tamed with bands of railroad stretching from coast to coast, and now the traveler has it easy. He's just taking advantage of this new technology and infrastructure to enjoy himself and really experience the country.

No comments:

Post a Comment