As much as Lummis loved Golden, he would chose a different place to go near Albuquerque years later when he needed a refuge. When Lummis finished the Tramp, he literally went to work the next day at the Los Angeles Times. Lummis was a workaholic, keeping up the intense expenditure of energy he performed on the tramp. As the hard-working editor of the LA Times from 1885-1888, he consistently burned the midnight oil grinding out the daily paper. Eventually, his incessant work caught up with him and he suffered a stroke that partially paralyzed his left arm and leg. He decided to leave Los Angeles and recuperate on the ranch of his good friend Amado Chaves in San Mateo, New Mexico.

While living in New Mexico he observed and reported on the corrupt machinations of a powerful old guard New Mexican family. In an article published in the LA Times he accused the family of being behind the murder of an elections worker on Election Day 1888. Townspeople in San Mateo told Lummis and his host that a peon from Mexico had been paid to assassinate them.

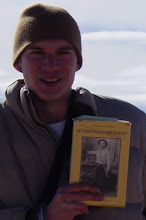

As Mark Thompson puts it in his biography of Lummis, The Curious Life of Charles Fletcher Lummis, "He didn't have a death wish, some of his conduct over the years notwithstanding." Even before the article was published, Lummis had been looking for a place to escape from the threats on his life-- but he evidently still wanted to stay in New Mexico. He chose a place he visited only briefly on the Tramp: the Isleta Indian Pueblo.

Another Silly Gringo in Their Midst

It's always good to let people know what you're doing, because you never know when someone can help you out. While on the road I got an email from my aunt in Tucson that they had a friend who worked in the medical clinic at Isleta, and would I be interested in having her show me the reservation? So the morning after tramping around Golden I got to visit Isleta.

I had to get up early to follow my host into work on the reservation. Soon after getting off the highway and entering Isleta, I found myself pulling all my worldly possessions through a confusing tangle of dirt roads, surrounded on all sides by a mixture of low, earthen colored one-story adobe houses, mixed with low modern buildings. Neatly packed dirt. That's one thing I will always associate with Iselta.

But let me stop here. I didn't really get to experience Isleta during this first, quick visit. I didn't have time to meet any Isletans, didn't get to walk around much of the main plaza, or explore the pueblo, so I can't really give you a steel pen sketch of the place. I don't want to romanticize it by describing the rambunctious young black and white puppy that ran across the plaza to greet us when we arrived. But I will say I doubt it has changed much since Lummis lived there. And I did get to do something really incredible: I was given a tour of the old adobe Catholic Church at Isleta, built in 1710. And I was honored with a meeting with the priest at Isleta, who personally showed me around the church and many of the ancient artistic objects-- a tribute certainly more to my host than to myself.

My kind and wonderful host in Albuquerque, Bee, had to leave me before the appointed time for the meeting with Father Hillaire. When I entered his office I was greeted by a kind-looking man you would guess was a college professor. And indeed he could be a professor with his Ph.D. in Linguistics. Bee mentioned that one of the things that first struck her about Father Hillaire was hearing him deliver a Mass in Southern Tiwa, the indigenous language of Isleta.

Bee gave me some great background on the pueblo over dinner the night before, and in the morning gave me a prep on behavior on the reservation: no pictures, and you can look but don't climb up on the kivas (the religious ceremonial chambers, entered through the roof via ladder). I don't mind about the pictures, and actually I respect it.

From Albuquerque, Lummis went west into northern Arizona. Northern Arizona is not characteristic of the rest of the southern part of the state. It has high mountain ranges that get blanketed with snow, and Lummis indeed encountered lots of snow on his tramp. 2010 was no different. The last, and biggest of three snow storms rolling through the Southwest was about to hammer northern Arizona. With my experience with the last two storm systems, I was ready to call it a day. As much fun as I've been having, I'm eager to land in Phoenix and begin my life. I actually discuss driving routes with Father Hillaire, and he confirms that the best way to get to Phoenix would be to take I-25 South to I-10, then take that the rest of the way. I-10 will get me to Phoenix far to the south, safely away from the snow.

So Father Hillaire leads me back out of the reservation (we were both concerned I might get lost trying to get out). It was a quiet, apt way to end the Re-Tramp, for now. I make a quick Starbucks stop, then hit the road hard, with near continuous driving for 7 or 8 hours to Tucson, where I stop for the night. At some point along this long pull I start seeing saguaros, signaling that I am in the Sonoran Desert.

Final thoughts

Going into this driving tour of Lummis's walking route, I definitely had expectations about what I would find and write about. I expected to find a West radically transformed in the 125 years since Lummis walked it. I expected to find shocking differences that might reveal startling things about our modern world. I expected to report on an overhauled West.

But just the opposite happened. I found myself constantly surprised by how much was still the same as Lummis's account. Sure, a lot of things are different, but I found the basic outlines drawn in the Tramp Across the Continent to be surprisingly intact. Some of the things I came across were crumbling ruins, but I also came across things that are still living institutions 125 years later. It seemed like I couldn't avoid stumbling into some of the same situations Lummis did, merely by retracing the same basic route.

In a lot of ways it seems like the country has merely built up along the lines described by Lummis, and not so radically transformed in the intervening 125 years. Denver, though it has swelled since Lummis visited, is still a dot of civilization on the edge of the vast plains. Mountains and mountain passes are still formidable obstacles. Even one of the biggest changes, the birth of cars and roads and the demise of horses and trains, did not strike me that forcefully: I was driving my car along historic railroad lines, connecting cities that were formed around railroads, rivers, and wagon roads. I defy someone to drive on Route 40 in Western Kansas, drive in and out of the tiny cities, like pearls on a string, that Lummis mentions, and tell me this place has radically changed since 1884.

If you committed a crime in Colorado in 1884, there's a good chance you were sent to Cañon City. If you commit a crime today, you will probably still end up Cañon City. If you are a Native American seeking advanced education, you may follow in the footsteps of generations of scholars and high yourself to Lawrence, Kansas. I visited a brewery in Golden, Colorado, today one of the world's largest, that was brewing beer in the same place it was when Lummis came through Denver. I got to the top of Pikes Peak on a train that's been running since 1891.

Maybe we are not as revolutionary as we think, and are more deeply rooted in the past than we believe.

All in all, in case I haven't shown it in my last few posts, the way the country slowly changed and unfolded was incredibly powerful for me. The route was like a plot line in a drama about the Continent. Different emotions are pricked at different times. The country says different things to you at different times. It builds you're suspense as you speed west towards the Rockies. It whispers in your ear soothingly as you coast down the cozy space between the plains and the foothills, and sends you soaring as you reach Pike's Peak. Then your pulse races when you try to cross the mountains. I could see easily how this route transformed and inspired Lummis.

Thanks for Reading

I'd like to thank everybody who has read this blog (especially if you are still reading this post!) The blog made this amazing trip even more fun for me. Your comments and notes meant a lot and were much appreciated. Don't be surprised if you get an email about another blog sometime, and I will appreciate your patience with this spam email.

Love ya,

SHU